Experimenting With Yeast

All of our food comes from the living world around us. Most of it it is made from plants and animals, but other living things go into our food, too. Today, we’re going to explore one of these other ingredients, called fungus (if there’s only one, we call it fungus; if there are many, they are fungi). Fungi are found nearly everywhere and play important roles in our world. They can help break down dead plants and animals, returning them to the earth. Some fungi can cause diseases. And there are some fungi that we eat, like mushrooms.

About the Experiment

About the Experiment

For this experiment, we’re going to learn about a very small fungus, called yeast. You can’t see a single yeast with your eyes, but if you put a lot of yeast together, you can get a gooey lump (if they’re wet) or a powder (if they’re dry). Yeast are one of the most important ingredients in bread. Let’s find out how this special fungus helps us make bread.

|

Details

|

|

|

|

|

What You'll Need

What You'll Need

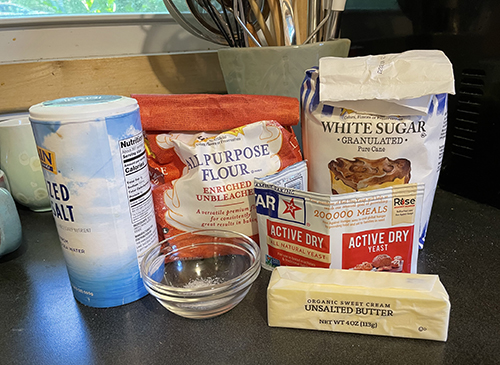

- Measuring cups and spoons, bowls, mixing spoons, 2 baking pans, oven

- Active dry yeast

- Flour

- Warm (not hot!) water

- Sugar

- Salt

- Butter or similar product to grease pans

Let's Do This!

Let's Do This!

The yeast you buy in stores is alive. It may not seem like it because it’s just a dry powder, but the yeast are just resting, until we tell them it’s time to wake up and get going. How do we do that? Just add a little water – and sugar.

- Begin by preheating your oven to 450 degrees.

- Activate the yeast by mixing it with ¼ cup of warm water and a teaspoon of sugar, then wait for about 15 minutes. In a second bowl, add just the yeast and water, but no sugar. Does the yeast react the same way with or without the sugar? Why do you think this is happening? (After observing the two mixtures, discard the one without the sugar)

- Mix 2 tsp of yeast with 3 cups of flour and 2 tsp of salt. Add another cup of warm water. Stir until it’s all combined into a doughy blob. If needed, add a little more warm water until the mixture sticks together. In a separate bowl, mix the same ingredients – but without the yeast.

- Cover both bowls and leave them out at room temperature for 2-3 hours. The room should be warm, at least 70 degrees. What happens to the mixture in each bowl at the end of the time?

- Sprinkle some flour on a table or surface to shape the dough, then place the dough on top of it. Fold the dough into a round shape, then push down on it to squeeze out the air bubbles. Do this once or twice more. Repeat with the other dough.

- Grease the inside of the pans with butter or a similar product and place the loaves into the pans. Note which pans have the dough with and without the yeast.

- Bake for 30-40 minutes, checking periodically to see how the loaves look. Watch their color and take them out when they begin to turn golden brown. Let them cool for about 10 minutes before cutting into them. What does each loaf look like when you cut into it? How does it taste?

What Did You Learn?

- What happened to the loaves with and without the yeast? Why?

- Did the two loaves taste different? What about their texture (how they felt)? Would you want to eat bread made without yeast?

- Is what happened to the bread the same as what happens when soda or other drinks have bubbles in them? How is it the same or different?

- What the yeast did with the sugar and the water is a process called fermentation. The yeast changed the sugar into a kind of gas, called carbon dioxide. Do you think any of the other foods that you eat are made using fermentation?

Resources

To see how else scientists are experimenting with yeast, check out the resources below.

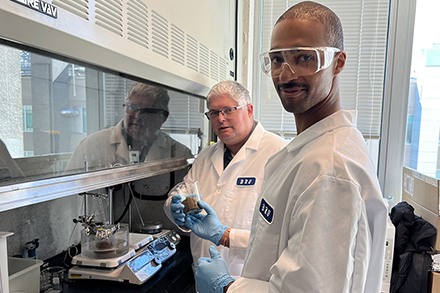

It’s not just for food – some scientists are using yeast to make fuel for cars too.

Yeast might even help feed astronauts in space.

Where does the yeast we use in baking come from?

Scientists are exploring whether foods made with fermentation are especially good for us, by helping to feed the bacteria in our stomachs. Bacteria are living things that are too small to see, but all around us.